Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Palestinian designer Samer Selbak looks to his love for nature and his rich heritage to remind us that design is a powerful tool for change

This interview with Selbak reveals his exploration of the indigenous Lufah plant and its design applications

Can you tell us a little bit about your background: where you grew up and how/if your heritage plays a role in your work as a designer? I was born and grew up in Shefa-Amr, between Nazareth and Haifa in northern occupied Palestine. My family has always kept a very strong connection to nature, be it through our olive trees, our tradition of foraging, or simply our love for spending most of our time in our surrounding nature.

My first memories are [of being] in nature with my mother and grandmother, walking for hours in the nearby forest, looking for edible plants, wild fruits and vegetables. This has shaped my love for and connection to my environment; learning the names and the traditional uses of each and every kind of plant and tree, how to forage responsibly and how to prepare it for consumption or use, and what to cook with it. These occasions allowed me not only to learn more about the history of my culture, but also to share precious moments with the women of my family, hearing their stories and learning to develop a particular sensitivity to the details in my surroundings.

I grew up being exposed to different cultures: On one hand [was] a traditional Palestinian lifestyle, preciously preserved by my grandparents and shared with us through storytelling, traditions and different activities around food and nature. On the other hand [was] a reality of living in an occupied place where you must always question conventions and fight for your place and for your own truth, and to find different types of compromises and inventions to react to those cultural clashes.

Growing up, I was both fascinated and frightened by these two contradictions, thinking I could only exist in one of these extremities. Today I know that it is part of who I am, part of what enriches me culturally and personally, and what allows me to always see reality in a much more intricate manner. In my work as a designer, I would like to think that this rooted knowledge and sensitivity that I acquired, be it towards nature or towards my culture and traditions, allows me to see things from a personal perspective. That’s why there is always a place for nature, animals, tradition and people in my work.

Do you have any anecdotes that you can share that perhaps show your early interest or curiosity for design? My curiosity actually began with photography. My mother used to love taking pictures of us, her kids, and of the daily life around her. Soon enough, I managed to buy my first camera from my pocket money, and since then I’ve never left it. I think this was the preparation stage prior to becoming interested in design. I was observing life around me, as well as observing and questioning my own belonging to my surroundings. I think my mother brought to all of us a certain sensitivity and inclination towards beauty, and it too was present in anything she did with us – from how we dressed to the pastries we would make. I always helped at home with pastry-making and anything that had to do with creating perfect shapes that demanded a lot of attention to details, especially in my family where perfectionism is a shared curse. Both my mom and my dad were always good with their hands, and very much creative people. I guess this has left a mark on me as well.

You mention that your work connects aesthetics with politics. Can you expand a little more on that and give an example of where this intersection is present in your work? Being Palestinian has so many different ways of showing up in your life choices or your work. There will always be politics in anything I create, even though I prefer to think about my work [as being] beyond politics, and that it is somehow naturally woven into it.

I think that through aesthetics we can tell a story that can resonate with different people, and by doing so we can introduce or treat a political subject without it being the centre [of the work]. I do not find politics to be particularly beautiful, but I do think that design and art can be powerful tools to raise such questions. Sometimes showing certain types of beauty can be a political act.

In my work, there is always a story that connects the aesthetics with the political and cultural aspects, altogether. The Luffa project, for instance, was born from the idea of having an indigenous plant that used to be an everyday part of Palestinian culture, and that I stopped seeing around while growing up. It all began with a memory I had from my childhood, of seeing the huge Luffa fruits at my grandparents’ yard, which were bigger than me, and wondering why they disappeared. I wanted to remind my people of it, and to use it in a way that is different to its traditional use as a natural sponge.

It is always very emotional for me to see how the simple fact of working with this material reminds people of its existence, brings back old memories and resurfaces a forgotten interest and love for something we were in the process of being alienated from. I’ve had numerous encounters where people came up to me and told me how much it moved them to see these designs because it brought them back to their own childhood memories. When a woman from Morocco tells me it brought her back to her own family memories, it is definitely political; it’s about bringing people together through our shared experience and about finding a way to keep this precious thing alive.

Do you think design could be used as a tool to inform about bigger world issues and do you think it is being utilised enough within that sphere? I think the design world is changing right now, from a white-dominated field to a more inclusive and open environment. It’s quite a challenge finding your way into a well-established field when coming from a less privileged part of the world. You have to stand behind your ideas and beliefs even when you’re all alone. You have to fight harder to express and insist on your point of view, because sometimes you find yourself in front of someone who comes from a very different cultural background. Living in Paris for the last eight years has taught me many things, especially how to appreciate and value my own distinctiveness and how to turn it into my power. Not fitting in was always where I’ve fit in, and it becomes a blessing when you learn how to manage it. Design is an amazingly powerful tool that can have a concrete impact on people and on life in general. It can create real change, especially within marginalised groups and in cultures that have been long left out of the conversation. The impact of the design world on the environment and on the planet is huge as well, so we need to assume responsibility as designers and do everything we can to work towards a change.

I think that people who are marginalised need to find endless ways to survive and adjust, to question the dominating cultures’ conventions and to work around them, instead of living by them. It is so important to listen and learn from people who do not fit into the main culture that controls the narrative. This is something that needs to be taught and encouraged – and we can already see its positive impact, changing our reality for the better in every field.

We should be working on creating a future that includes everyone, and that asks all the questions prior to making choices that could end up affecting humanity as a whole. We see it very clearly today: how the vanity of Western capitalistic logic leads to horrible consequences. We already understand what we get when we do not practice this kind of openness and consideration: a world full of injustices and inequality that profits only a fraction of humanity. But I think that there is much work ahead – the fight has only begun.

Can you tell me more about your interest in tradition and what that means to you? I remember how I used to be afraid of tradition when I was younger. I always tried to run away from it and run towards the Western world’s ideas and values. With time I got to see and experience how our traditions were destined to be ridiculed and reduced into stigmas and racism. From this moment on, I started seeing and discovering the beauty in traditions, questioning myself about choices and ideas that I’ve adopted, and that were forced onto our cultures.

With design as a tool, I aim to shed a different light on the beautiful parts of our traditions, rather than continue living by what the West had imposed on us and what we might have internalised ourselves. I hope to empower my people and to show the world how these ideas and practices, that have been surviving for hundreds and thousands of years, should be appreciated and could help in building a better world. When you see the difference between the way in which tradition and indigenous knowledge affect the way a group treats its environment, understands it and works with it instead of against it, you begin to understand the importance and the power of such things. I always joke with my family about how, with every year that goes by, I understand more deeply how my grandmother is always right. Our elders know best, and we should never forget or fight that. As newer generations, we should be critical of old ideas that may have expired, and re-examine and rethink some traditions, but all the while we must listen carefully and respectfully to our predecessors. Many of them hold so much intelligence and can help our generation create a better reality.

What intrigues you about natural materials and how do you relate that to your interest in tradition? Working with natural materials means entering into a very intimate relationship with the material. Unlike industrial materials, where the whole production system is defined and the rules are clear, natural materials demand a deeper understanding. You have to discover everything on your own and instead of imposing your ideas on it, you must first let it teach you about itself. Thanks to this long journey of discovering, you have the chance to be critical of your choices, be it the production process, the material use, the waste you create, etc.

When you work with a natural material, it obliges you to be very creative during the different stages of the process: where to find the material, how to treat it, what to do with it, and how to appreciate its natural characteristics. You develop a different kind of respect for the material and hence for the work you do with it.

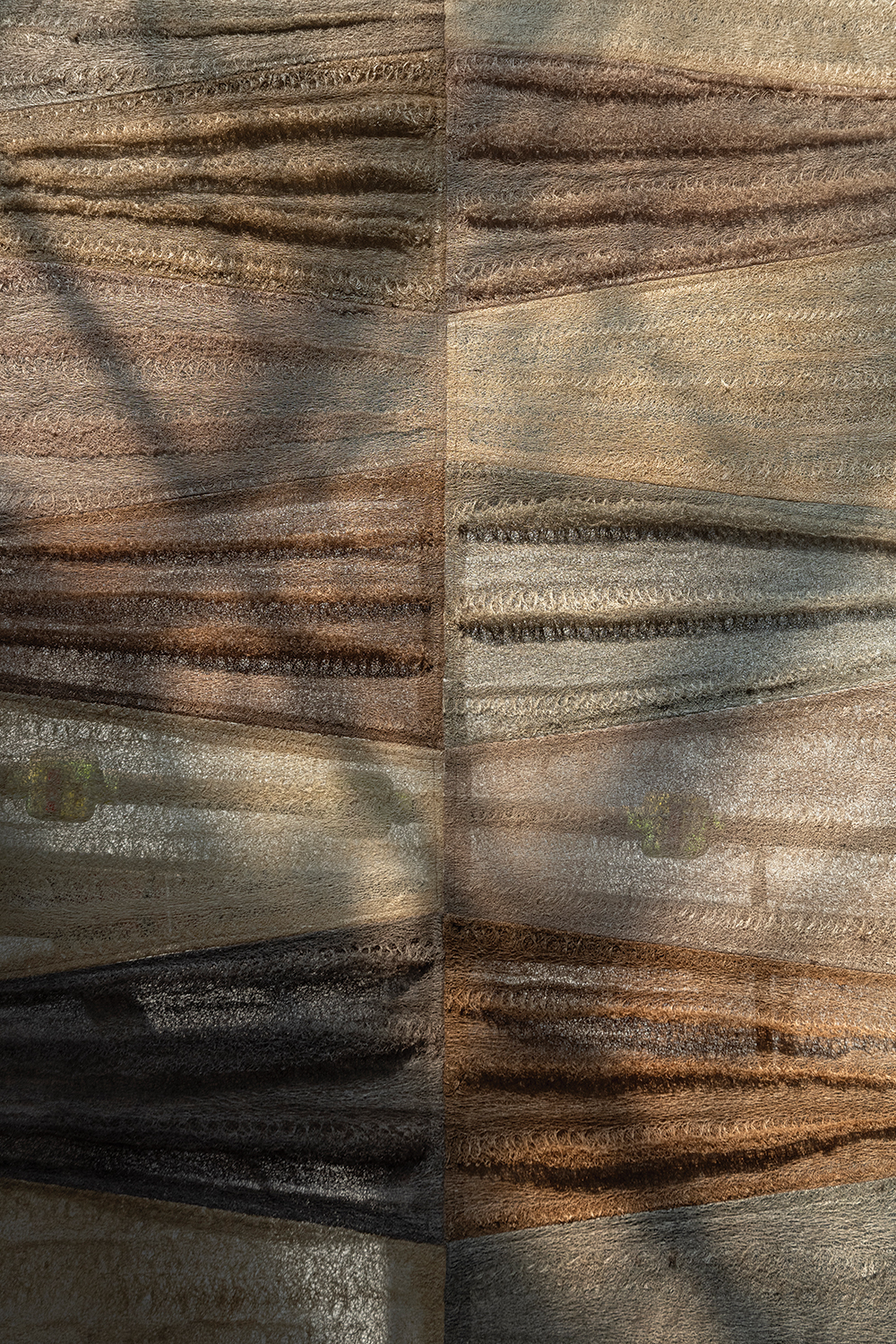

Working with Luffa, for instance, was very complex. Since I was so used to thinking about it as a bathing sponge, I needed to break free from my mind’s restrictions, to observe it and play with it and to challenge my imagination. Then [I moved to] researching the material, studying its behaviour, appreciating its strengths and accepting its weaknesses – it all demands a lot of patience and trial and error. But after all the difficult moments of failure, when you finally discover something about the material, when you succeed in valorising it, it is a different kind of payoff. It’s a strange feeling of excitement and accomplishment that I’ve never experienced before while working with industrial materials. This is the intimacy that I speak of; it’s between you and your discoveries and it feels like the synthesis between the human imagination and the great powers and restrictions of nature. It was imperative for me to respect the natural aspect of the material, and not to force anything on it. That’s how I started researching natural dye as a technique, in order to achieve the aesthetic that I had in mind, by extracting natural pigments from different plants and vegetables, which are traditionally used for the same purpose in Palestine. I think natural materials and tradition are deeply connected and they feed off each other. It is the special relationship between natural materials and tradition that interests me and enriches my work, and it is in the back and forth between the two that I find inspiration.

Can you tell me more about your Luffa project? The Luffa project began with a feeling of longing for a receding memory of the Luffa plant. I wanted to find a way to bring it back to people’s thoughts, and today I see how it brought it back into their hearts more than anything else. Many of my friends, family and the people I’ve met while working on or showing my work have been suddenly planting and growing Luffas as a result of seeing this project. I find that amazing and it fills my heart in so many ways.

From this souvenir, it then quickly turned into a project that has nature at its centre. I am always in awe of nature, and this was an opportunity for me to pay homage and express this awe by way of design. I am often saddened by our detachment from it as human beings, and I wanted to bring natural and wild elements back into our lives and our homes. I would like for my pieces to be able to raise awareness about what we’re doing to the planet, to other animal species, and to ourselves.

The project began with two different sculptural pieces: Saffeer which is a pendant light, and Reef, a space divider. Since then, I’ve been working on developing new forms and new material combinations, one of them being the Luffa ceramics that I am developing now.

Aside from the process of understanding the material, I went through a long formal process of playing with texture, transparency and shapes, in order to come up with a new aesthetic. So, if the material and its treatment evoke tradition and nature, the shapes express innovation and experimentation. I think this synthesis is a very accurate self-portrait.

With the Luffa ceramics, can you expand a bit more on your material exploration and what stage you’re at? The Luffa ceramics [project] is an ongoing material research revolving around Luffa fibres and ceramics, in which one suspends the other in time, creating a fossil-like material and shapes. I’m interested in creating objects that evoke the idea of living organisms frozen in time. The next stage for this project is to find funding, and partners to develop it with.

It is obvious that the natural world is of importance to your work and drives many of your projects. Can you tell me more about your intention of working with a ‘sustainable’ approach? I think that working with a sustainable approach should become one of the bases for designers today. I always come across these questions while working on anything, as it is my responsibility to create with awareness and to learn how to find new and alternative ways to solve problems and how to think deeply about consequences. Personally, I feel much more accomplished when I challenge myself to find creative ways not only to not harm the planet, but also to benefit it. I am always humbled by what I can learn from nature, animals and long-proven sustainable methods and practices.

For me, design becomes much more interesting when it serves those without a voice, or those facing difficulties. That’s why I would like to continue exploring ways in which I can take care of wildlife, for example, in my future work.

How do you see the role of the designer today, and how do you see your own work reflecting this direction? The designer today is a person who thinks not only through values of aesthetics and profits, quantities and power. It is a person who has a great responsibility towards other people, from different parts of the world and societies, responsibility towards the environment, and respect for different approaches and beliefs. Someone who is capable of listening, questioning and learning while exploring their ideas and work. I aspire to continue my exploration of finding new ways to design, to always ask the difficult questions and to be critical of the choices that I intend to make. There is so much beauty in simplicity, and I feel like the world has always been generous with us human beings and has always provided us with more than we need. I hope we stop exploiting and exhausting the planet’s limited resources and accept that it is time for us to appreciate what there is, and make the best out of it.

The Latest

Textures That Transform

Aura Living’s AW24 collection showcases the elegance of contrast and harmony

Form Meets Function

Laufen prioritises design, functionality and sustainability in its latest collections

Preserving Culture, Inspiring Creativity

Discover the Legacy of a Saudi Art Space: Prince Faisal bin Fahd Arts Hall explores the Hall’s enduring influence on the cultural fabric of Saudi Arabia

Channelling the Dada Spirit

Free-spirited and creative, The Home Hotel in Zurich injects a sense of whimsy into a former paper factory

id Most Wanted- January 2025

Falaj Collection by Aljoud Lootah Design

Things to Covet in January

identity selects warm-toned furniture pieces and objets that align with Pantone’s colour of the year

Shaping the Future of Workspaces by MillerKnoll

Stacy Stewart, Regional Director Middle East & Africa of MillerKnoll discusses the future and evolution of design in workspaces with identity.

Shaping Urban Transformation

Gensler’s Design Forecast Report 2025 identifies the top global design trends that will impact the real estate and built environment this year

Unveiling Attainable Luxury

Kamdar Developments has launched 105 Residences, a new high-end development in Jumeirah Village Circle.

The Muse

Located in the heart of Jumeirah Garden City, formerly known as ‘New Satwa’, The Muse adds to the urban fabric of the area

Cultural Immersion Meets Refined Luxury

The Chedi Hegra opens its doors in AlUla’s UNESCO World Heritage Site

Redefining Coastal Luxury

Sunshine Bay on Al Marjan island combines seaside views, exceptional design, and world-class amenities to create a unique waterfront haven