Copyright © 2025 Motivate Media Group. All rights reserved.

Celebrating 100 years of De Stijl

We are chronicling the people, places and objects that will stand the test of time.

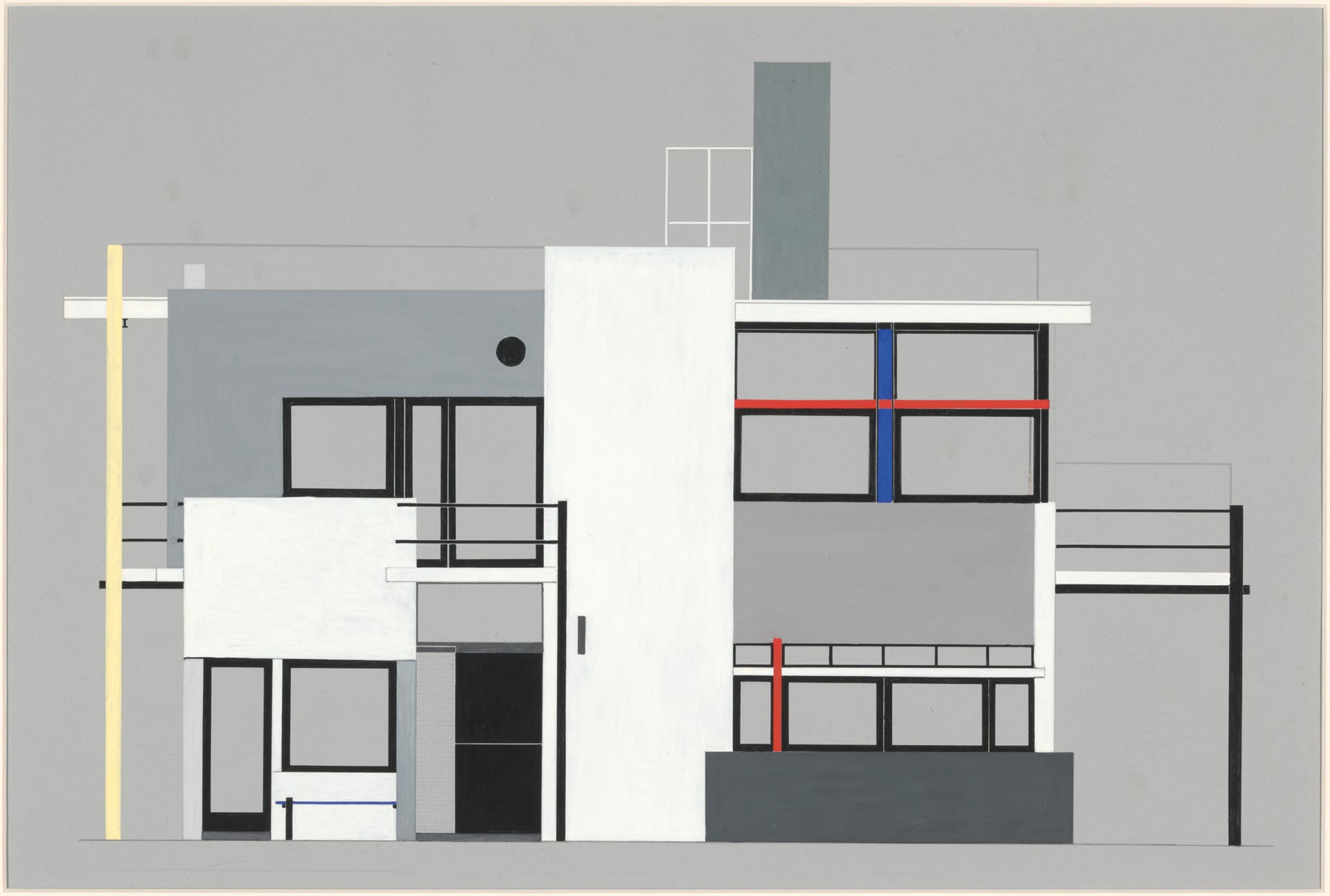

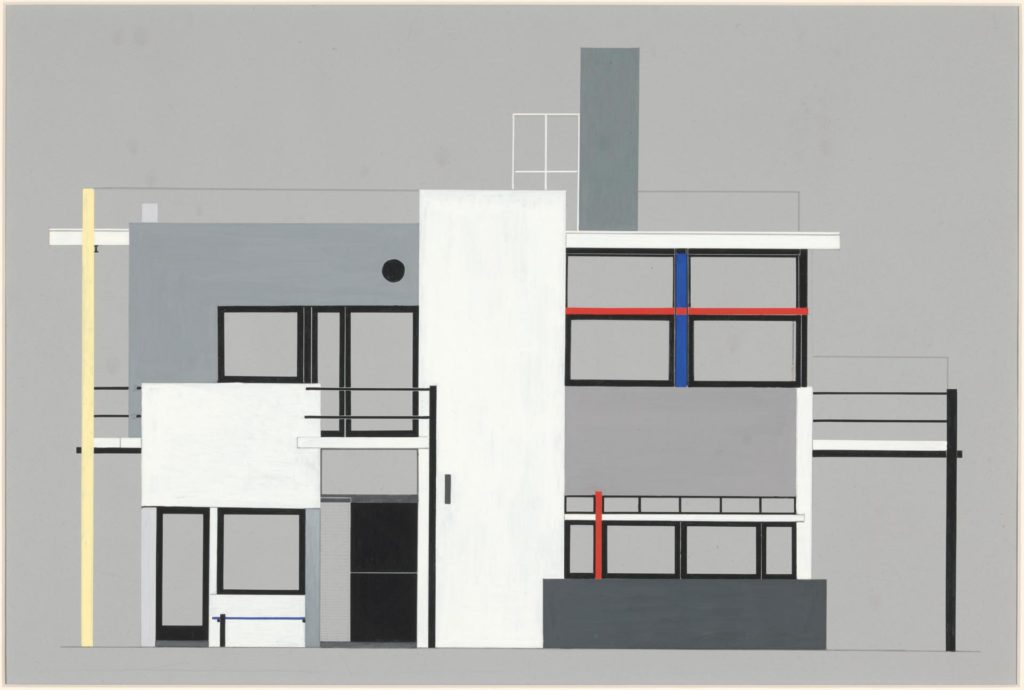

Neoplasticism is an unfamiliar term to most, yet plenty will know its more common name: De Stijl (literally ‘The Style’). The hugely influential artistic movement began in 1917 in the Dutch city of Leiden and was unusual in its determination to embrace simplicity.

De Stijl was characterised by its desire to express a new ideal of order and spiritual harmony, and by its advocacy of reduction to essential forms and colours: only vertical and horizontal elements were initially used, and only black, white and primary colours.

The movement consisted of artists and architects, and its principles were therefore seen as being equally applicable to both disciplines, and beyond. Perhaps the most famous member and proponent of De Stijl was Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), the Dutch painter who created the renowned works that have inspired designers working on everything from Yves Saint Lauren clothing to hair product packaging.

Mondrian’s most famous grid-based pieces were very simple in their composition, and rigid in their adherence to the movement’s principles. Later, however, Mondrian showed the versatility of De Stijl, using a greater variety of angles and colours – particularly in the works that were in progress or finished shortly before his death.

Indeed, this evolution has expanded the influence of De Stijl, as ‘colour-blocking’ – a freer, more flexible interpretation of principles – continues to find popularity among designers of buildings, clothing, jewellery and furniture.

One of the original aims of De Stijl was to deliver impact that went far beyond only painted works. Its earliest members included architects J. J. P. Oud (1890–1963) and Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964) – and it was the latter who created the Red and Blue Chair of 1917 that’s pictured here.

Just one building was created completely in accordance with De Stijl principles – the Rietveld Schröder House – yet the movement influenced architecture greatly for many years afterwards, such as Oud’s Café De Unie in Rotterdam and the Eames House by Charles and Ray Eames.

For final proof of De Stijl’s continuing and widespread influence, Moscow Metro’s Rumyantsevo and Salaryevo stations, which opened last year, feature design aesthetics inspired by the principles established a century ago.

The Latest

Textures That Transform

Aura Living’s AW24 collection showcases the elegance of contrast and harmony

Form Meets Function

Laufen prioritises design, functionality and sustainability in its latest collections

Preserving Culture, Inspiring Creativity

Discover the Legacy of a Saudi Art Space: Prince Faisal bin Fahd Arts Hall explores the Hall’s enduring influence on the cultural fabric of Saudi Arabia

Channelling the Dada Spirit

Free-spirited and creative, The Home Hotel in Zurich injects a sense of whimsy into a former paper factory

id Most Wanted- January 2025

Falaj Collection by Aljoud Lootah Design

Things to Covet in January

identity selects warm-toned furniture pieces and objets that align with Pantone’s colour of the year

Shaping the Future of Workspaces by MillerKnoll

Stacy Stewart, Regional Director Middle East & Africa of MillerKnoll discusses the future and evolution of design in workspaces with identity.

Shaping Urban Transformation

Gensler’s Design Forecast Report 2025 identifies the top global design trends that will impact the real estate and built environment this year

Unveiling Attainable Luxury

Kamdar Developments has launched 105 Residences, a new high-end development in Jumeirah Village Circle.

The Muse

Located in the heart of Jumeirah Garden City, formerly known as ‘New Satwa’, The Muse adds to the urban fabric of the area

Cultural Immersion Meets Refined Luxury

The Chedi Hegra opens its doors in AlUla’s UNESCO World Heritage Site

Redefining Coastal Luxury

Sunshine Bay on Al Marjan island combines seaside views, exceptional design, and world-class amenities to create a unique waterfront haven